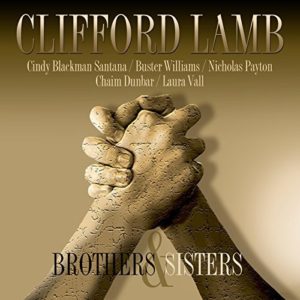

On Brothers & Sisters, Clifford Lamb builds upon his previous release to further bridge the several streams that flow together in his music: his work as a composer; his flair for arranging music written by others; his abilities as an improvising pianist, working with first-rank collaborators; and his desire to incorporate newer developments into a style and career steeped in the jazz tradition. Add in a concern with matters of fairness and justice, and that’s a lot to pack into 25 minutes. Yet this set feels neither rushed or overstuffed – a testament to the purpose and command at the heart of these songs.

Take the title track, for example. Although inspired by recent events – a political campaign that has exposed the deep divisions in American life – it in fact could have sprung from pretty much any epoch in the history of man.

Spanish-born vocalist Laura Vall (of the indie pop band The Controversy) provides the ethereal introduction, aided by Cindy Blackman Santana’s shimmering cymbal work. Then Lamb and the legendary bassist Buster Williams fill out the groove, setting the stage for poet Chaim Dunbar to remind listeners of a message that always needs restating: “Unaware of our family ties,” raps Dunbar, “we become complicit in our own demise.” Adds Lamb: “It reflects the urgency I feel about what’s going on in the world, politically and socioeconomically, along with my feeling about how people should ideally be getting along. We’re all the same, and we should address each other as human beings first.”

A similar plea for inclusiveness and communication characterized “What’s Going On” – Marvin Gaye’s signature hit record of 1971 – and appropriately, Lamb’s version of that song comes right after “Brothers & Sisters.” You might have a little trouble finding

the melody, because Lamb has rewritten the song’s harmonic structure to shroud the familiar theme; when you do hear it, peeking out from the new chords, it carries a little jolt of unexpected recognition, and you hear the tune anew.

At first glance, the title “Red And Blue” might also appear to have a topical basis, but in fact, Lamb wrote it years ago, with lyrics that traced a story of unrequited love. He admits that the title makes it a serendipitous choice for our politically divisive time; so does the light jazz-rock shuffle that animates the solo, one of Lamb’s best solos – not only for the elevated quality of the improvisation itself, with its rhymes and echoes, but also for the

interaction among the trio.

Lamb’s ability to get inside other composers’ works comes to the fore on the two solo piano pieces, “Kamala’s Dance” and “Fair Weather,” both of which have a trumpet connection. The rhapsodic “Kamala’s Dance” has been recorded only once before, by its composer Roy Hargrove, and only as a digital-edition “bonus track” to his album Earfood; Hargrove wrote it for his then five-year- old daughter Kamala, and Lamb invests it with the playful grace of childhood. And he first heard the haunting “Fair Weather” on a recording by the polymath hornman and keyboardist Nicholas Payton; “It just blew me away,” he remembers. (Don’t confuse this lovingly portrayed song with the swinger of the exact same name composed by Benny Golson; this one, composed by Kenny Dorham in the mid-50s, gained new admirers when it was featured in the film Round Midnight.)

Payton himself takes a turn on the sparky, hard-driving album opener, “Hold The Line,” filling the track with molten brass and spinning an adventurous solo that travels far but returns to where it started. Lamb wrote the song shortly before the recording session, and specifically with Payton in mind; he titled it with a metaphor for staying strong to one’s convictions. “I wanted to do something reflective of all the listening I’ve done

to Nicholas’s music. I’ve transcribed a lot of his tunes, and used many of them on my gigs here,” says the pianist, referring to his recurring appearances at San Francisco’s Jazz Bistro. While Payton’s reputation as a trumpeter speaks for itself, relatively few listeners have delved so extensively into his writing. But Lamb’s embrace of these compositions has elicited what he calls a “symbiotic” attachment to them, “and they get a very strong response from an audience. They’re modern and bluesy at the same time.”

Brothers & Sisters is the second of Lamb’s “cameo collections,” short

albums of six or seven tracks that present a digital-age version of the vinyl

era’s EP (Extended Play) discs. These allow Lamb to follow the lead of hip-hop and pop artists who – unburdened by the directive to complete a full-length album for each release – can intensify the relevance of their music by shrinking the gap between creation and consumption. As with the previous release Bridges, Lamb recorded direct to two-track, with no post-production tweaks to amend what took place in the studio. What you hear is what they played.

And because these mini-albums arrive more frequently, you can better gauge Lamb’s progress in channeling a new river of music from the different tributaries that feed his imagination. “This has got a little bit different energy than the first one – a little more urgency, and it’s little more mainstream,” he allows. “The craftsmanship has more of a crisp edge. And because of the way Cindy and Buster put it all together, it has a little but more drive.”